Artist Highlight: Henry Ossawa TannerNavigating the Canvas as a Black Artist in a Divided World

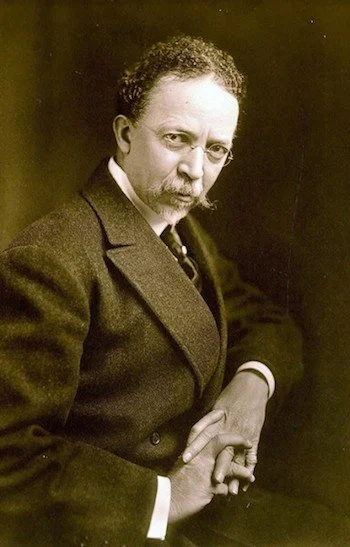

At the 9th Floor Artists Collective, we honor the artists who not only mastered their craft, but who used it to assert their humanity in the face of systemic injustice. Few figures embody this more powerfully than Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937) — a visionary painter, a spiritual thinker, and one of the first African American artists to gain international acclaim.

Rooted in Resistance

Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to Benjamin Tucker Tanner, a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, and Sarah Tanner, a woman who escaped slavery via the Underground Railroad, Henry Ossawa Tanner was shaped by a legacy of liberation. His parents instilled in him a sense of discipline, dignity, and spiritual purpose. These values would become the emotional and thematic foundation of his artistic career.

Though he was not enslaved, Tanner carried the memory of enslavement, faith, and survival in his bloodline. This inheritance manifested in his work—not through explicit political protest, but through a powerful insistence on the interiority, holiness, and depth of Black life.

Becoming a Black Artist in a White Art World

Tanner came of age during Reconstruction, a time when the promises of Black freedom were already being rolled back. He studied at the prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts—becoming one of the few Black students under the renowned realist painter Thomas Eakins. Yet, despite his talent, Tanner faced racial discrimination, ridicule, and barriers to exhibition.

The label of "Black artist" in America often came with limitations—expectations to either conform to racial stereotypes or be excluded altogether. Rather than submit to this, Tanner relocated to Paris in 1891. In France, he found a degree of artistic and personal freedom that was denied to him in the United States. There, he developed a style that blended Impressionism, Symbolism, and religious mysticism—and more importantly, he was seen first and foremost as an artist.

Yet even abroad, Tanner never abandoned his identity as a Black American. His most iconic painting, The Banjo Lesson (1893), was painted while on a return visit to the U.S. It captures a quiet, profound moment between a grandfather and grandson—both Black, both dignified, both rendered with care. This was not a cliché. It was a cultural declaration: Black people are whole, sacred, and worth portraying with respect.

Legacy Beyond the Canvas

Tanner’s achievements as a Black artist were not just individual—they were symbolic. He refused to become a “racial artist,” yet his very presence in elite art spaces disrupted racist norms. In 1923, he was named a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor by the French government—an honor never extended to him by the nation of his birth.

Though he did not align himself with political movements or speak publicly about racial issues often, his life was a statement: Black artists belong on the world stage. Our stories, our visions, and our talents are not marginal—they are essential.

At 9th Floor Artists Collective

We look to artists like Tanner as ancestral beacons—those who carved paths where none existed. His body of work reminds us that representation is not about mere visibility, but about being seen deeply. As Black artists and cultural workers, we carry forward Tanner’s legacy every time we choose to tell our own stories, shape our own images, and define our own worth.

Tanner showed the world that a Black artist is not a genre—he is a force.

May his courage continue to inspire us all.

Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937)

The Banjo Lesson, 1893, Hampton University Museum. Gift to museum by Robert C. Ogden.

The Annunciation, 1898 Oil on canvas, 57 “X 71.25”